The Rule of Law in Coronavirus Times

In times of crisis such as the one we are facing the rule of law is often one of the first casualties. The rationale for ‘bending’ or ‘breaking’ the law is that there is a greater need to protect life and property while ensuring that a stable State is maintained. The argument is that the right to life supersedes all other rights and that the State acts in the best interest of every citizen. Further, that there would be no State if its citizenry were wiped off the face of the earth.

Advocates of the rule of law are placed at a precarious situation; to champion for the adherence to the letter and spirit of the law or stay silent and allow the State to deal with the crisis in the best possible manner devoid of strict compliance with the law. Any person who questions the actions and intentions of the State is accused of not having the ‘best interest’ of the populace at heart or simply labelled as an enemy of the State. In such an environment there is an immediate chilling effect on the right to freedom of expression and freedom of the media. It is widely expected that all and sundry would unreservedly support the State.

From a study of history, this is a catch 22 situation. For example, after 9/11, governments embarked in a spirited and targeted scheme of unregulated mass surveillance, the rationale being that such mass surveillance was necessary for collection of intelligence and reacting to or averting terrorist attacks. Mass surveillance was not undertaken within any legal framework or the framework was weak, in fact existence of such schemes only came to light after revelations by whistleblowers.

The negative effects of creating a culture of operating outside the ambit of the law has been that mass surveillance has been used around the globe to silence government critics, activists, perceived enemies and political opponents. Definitely, 9/11 caused a radical shift in how fundamental rights and freedoms are interpreted by States where national security and public interest matters are concerned. Further back, the collective trauma that was occasioned by the effects of World War II had the effect of having States legislative international instruments to redefine rules of engagement in war and provide for an international Bill of Rights.

The post-Coronavirus era will bring with it a radical shift in adherence to the rule of law and maintaining constitutionalism. Before that happens, an analysis of how Kenya is maintaining the rule of law is key as an indicator of what may lie ahead.

A few days ago the Public Service Commission(PSC) advertised 5,500 positions for contractual health workers in the Ministry of Health and County governments. The Council of Governors, and rightly so have protested this move indicating that only the County Public Service Boards have the constitutional and statutory mandate to recruit staff for County governments. The contractual health workers are in principle meant to bolster the numbers of health workers who are currently managing the Coronavirus crisis. Hence, from a casual view the move seems well intentioned and for the public good. If the PSC went ahead with the recruitment, we could bet that County governments will seek to have the action annulled for being unconstitutional and a contravention of prevailing statutory provisions.

One question that may be asked from the above scenario is why County governments would be opposed to a recruitment that would perhaps help manage the current crisis in a better and efficient way. The answer is not as simple, but the fact is that this would create an environment and culture where National government would unconstitutionally usurp the powers and functions of County governments especially in a national crisis environment.

My view is that the impending impasse on the recruitment could be averted if PSC and County Public Service Boards jointly carry out the recruitment. This way none would argue that the other is usurping their constitutional mandates.

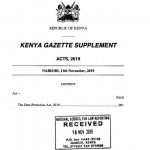

A second issue that has been debated is the place of privacy and data protection while dealing with a public health crisis. In my article Privacy, Data Protection and The Coronavirus I stated the following –

The challenge with the Data Protection Act is that it does not specifically define public interest. Perhaps, this is an intentional omission to provide for a broad interpretation of the phrase which in my view is subject to abuse. But, on public health matters like the CoronaVirus crisis we may rely on Section 46 and Section 51 that provides for exemption on processing of personal data necessary for public interest matters. Article 24 of the Constitution may also be interpreted to argue that limiting data subject rights in the prevailing circumstances is justifiable. This means that the State, any other data controller or data processor may lawfully collect and process data relating to the CoronaVirus.

But what should be the safeguards? We are guided by the Data Protection Act, 2019 and World Health Organisation directives on processing of personal data during health emergencies. Data processors and data controllers dealing with CoronaVirus data and in extension any health emergency data should ensure they –

Inform the public that personal data will be processed when the need arises; Safeguard the privacy, anonymity and dignity of individuals. In certain instances, personal data may be pseudonymised or anonymised; Safeguard people and populations from being stigmatised, discriminated upon unnecessarily or unfairly targeted; Ensure security of data; and Process the data only for the purpose of dealing with the health emergency.

Without a Data Commissioner, we have no idea whether the surveillance or data processing being undertaken by the State on persons of interest in relation to managing the Coronavirus is within the confines of the law. Are people informed that they will be tracked or their data collected? Are they informed of the reason for processing their personal data? The State has not provided any information to the public to inspire confidence in the security of the data. The State is operating in an environment that has no solid oversight mechanisms where data protection is concerned.

A third issue for consideration is the fact that the State has been managing the Coronavirus crisis without clear regulations. Only in the last week were the draft Public Health(Prevention, Control and Suppression of Covid-19) Rules, 2020 published. This is more than a number of weeks since the first Coronavirus positive test was made public. That the State would operate in such a manner makes its actions susceptible to legal challenge. However, indicated in the beginning of this article, such challenge may not easily materialize.

Lastly, Parliament has been eerily silent on providing oversight over the crisis. While the Ministry of Health may not provide the public with comprehensive information and data on how the crisis is being managed, Parliament has a constitutional mandate to provide oversight. To illustrate, there are questions being posed in the public domain about whether National and County governments have provided enough Personal Protective Equipment(PPE) to health workers, whether there are enough ventilators and ICU beds, whether quarantine facilities meet acceptable public health standard and whether there are sufficient social and economic safeguards in the event Kenya went into a total shutdown. Of course, the Ministry of Health has provided responses to some of these queries, but only Parliament carrying out its constitutional oversight mandate can verify such information and inspire confidence in the public.

The State should be granted maximum support in managing the Coronavirus crisis. However, this ought to be done within an environment that ensures adherence to the rule of law and basic principles of constitutionalism.

A very interesting perspective. State of emergencies and crises like the Corona Virus Pandemic are critical times in which democracy is tested. In this case, the legislative power has shifted to the executive. There is no democracy without a conception of the rule of law and the rule of law only works in democracies. Therefore, these are interesting times where the executive is deemed to the sole protector of public interest.

Maybe the article could have been titled

“Parliament, in a pandemic, a very brief history” OR “What is the argument for the rule of law in a pandemic“. Thanks though. You suggest many points for thought.

Great insight. Especially parliament abdicating its oversight function.

The rule of law is paramount if we are to leave in a democratic society. It is sad that during such crises the first item that takes a backseat is the rule of law. This is where human rights violations occur, all in the purview of so-called presidential directives. I hope we learn from past mistakes and since complete separation of powers is not possible, all agencies should work in tandem to ensure law in flux takes precedence in this Covid19 crisis.

An informative and balanced critique on the emerging human rights,governance, security and public health challenges. Yes there are more questions than answers now and we can only build scenario models in our minds to inform us on the probable or possible outcomes. Its a good piece that provokes legislative and Chapter 15 institutions active responses based on their specific mandates to be more proactive to assist the Ministries of Health, Social Security, Agriculture, Trade and Industry, Education, Interior and Coordination of National Government, Foreign Affairs , Labour and the County Governments in the planning, management, budgeting and monitoring of the unfolding public health situations and related issues (security, food, employment, etc). Lawyers are employed in both the National and County governments who would proactively guide in the drafting of regulations, legislation and policy in both ongoing and post COVID.

Both the CS Health and Interior have had to ‘recreate’ the ‘legal’ pathways as they go along to balance the social, cultural, economic and political interests and public interests too at times with mixed or negative responses. Its important to remember that Chap. 56 Public Order Act (Revised 2014) has never been overhauled in-light of the 2010 Constitution, therefore it has a different philosophical and political foundation. The Session Paper No. 3 of 2014 known as the Human Rights Policy (and expired Action Plan) is a good framework which the state can use during this difficult time to avoid judicial pitfalls or litigation.

Unfortunately, the 2010 Constitution especially Article 43 which is now the epicenter of COVID 19 threats is yet to be guided conclusively with policy and legislation that would assist the judiciary in interpreting the law, the legislatures in providing adequate oversight and the county in the interdependence balance with the national government (which is explicit when you watch the USA state/federal interplay and responses or requests) no wounder the silence!

The pending Dignity Bill, Whistle Blower Bill, draft business and human rights policy and the implementation of the Social Protection Act, PBO Act and National Coroners Service Act is a good place to start especially with the post COVID 19 to guide the recovery, remedy and reboot of all spheres of the peoples lives.

God guide and bless us all the Republic of Kenya. The words of the national anthem continue to inspire me,

O GOD of ALL creation

BLESS this our land and nation…

Let one and all ARISE

With hearts both STRONG and TRUE

SERVICE be our earnest endeavor…

Let all with one accord

In COMMON BOND united….

SELF QUARANTINE IF EXPOSED, SOCIAL DISTANCE, WASH HANDS WITH SOAP AND STAY AT HOME …